Introduction: The Power of Simplicity

Every smartphone, laptop, server, and supercomputer on Earth operates on a deceptively simple principle: electricity is either flowing, or it isn't. ON or OFF. 1 or 0. This elegant simplicity isn't a limitation—it's the very reason computers work at all.

At first glance, it seems absurd that devices capable of generating photorealistic images, predicting weather patterns, or understanding human language could be built from components that only know two states. Yet this binary foundation is precisely what makes digital computing possible, reliable, and infinitely scalable.

The Core Insight

Electronic circuits have natural resting states: current flows or it doesn't. By embracing this physical reality rather than fighting it, engineers created machines that could perform billions of reliable operations per second.

To understand why binary dominates computing, we need to journey from the simplest electrical device—the switch—through vacuum tubes and transistors, to the microscopic marvels inside your modern devices.

From Light Switches to Logic

Consider the light switch on your wall. It has exactly two positions: ON and OFF. When ON, electricity flows through the circuit and the light illuminates. When OFF, the circuit is broken and darkness returns.

Circuit open. No current flows.

Circuit closed. Current flows.

This binary nature isn't a design choice—it's physics. A switch is either making contact or it isn't. There's no "half-on" state in a well-designed switch. Early computing pioneers recognized that this all-or-nothing behavior could be harnessed for calculation.

Claude Shannon's Breakthrough (1937)

In 1937, a 21-year-old MIT graduate student named Claude Shannon wrote what many consider the most important master's thesis of the 20th century. He demonstrated that electrical switches could implement Boolean algebra—the mathematical system of TRUE/FALSE logic developed by George Boole in 1847.

"It is possible to perform complex mathematical operations by the manipulation of [relay] switches."

Claude Shannon, "A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits" (1937)

Shannon proved that by connecting switches in specific patterns, you could create circuits that performed logical operations: AND, OR, NOT. From these simple building blocks, any mathematical computation becomes possible.

The Vacuum Tube Era (1940s-1950s)

Mechanical switches were too slow for serious computation. Engineers needed electronic switches—devices that could turn on and off thousands of times per second without physical movement. The answer was the vacuum tube (also called a thermionic valve).

How Vacuum Tubes Work

A vacuum tube contains electrodes sealed in a glass envelope with the air removed. When heated, the cathode releases electrons. A control grid between the cathode and anode (plate) acts as a gate:

- Negative voltage on grid: Repels electrons, blocks current flow (OFF/0)

- Positive or zero voltage on grid: Allows electrons through (ON/1)

By varying the grid voltage, you could control whether current flowed—an electronic switch with no moving parts.

ENIAC: The First General-Purpose Electronic Computer

The Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), completed in 1945, demonstrated the potential of vacuum tube computing:

The Problems with Vacuum Tubes

Heat

Vacuum tubes generate enormous heat. ENIAC required industrial air conditioning and still regularly overheated.

Reliability

Tubes burned out frequently. With 17,468 tubes, ENIAC experienced failures multiple times per day.

Size

Each tube was roughly the size of a light bulb. Scaling up meant enormous machines.

Power

The electrical demands were staggering. Legend says ENIAC dimmed the lights in Philadelphia when switched on (though this is disputed).

Computing needed a better switch. It arrived in 1947.

The Transistor Revolution (1947-Present)

On December 16, 1947, at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, physicists John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley demonstrated the first working transistor. This invention would earn them the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics and fundamentally transform human civilization.

Why Transistors Changed Everything

| Property | Vacuum Tube | Transistor |

|---|---|---|

| Size | ~5 cm tall | Microscopic (nm scale today) |

| Power consumption | Several watts each | Nanowatts |

| Heat generation | Significant | Minimal |

| Reliability | Burns out in months | Decades of operation |

| Switching speed | Microseconds | Picoseconds |

| Manufacturing | Individual assembly | Mass production on silicon |

The transistor did the same job as a vacuum tube—acting as an electronic switch—but better in every measurable way. More importantly, transistors could be made smaller... much smaller.

How Transistors Actually Work

A transistor is a semiconductor device made primarily from silicon. "Semiconductor" means it can conduct electricity under some conditions but not others—making it perfect for building switches.

The MOSFET: Today's Dominant Transistor

Modern processors use Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors (MOSFETs). Here's how they function as binary switches:

No channel forms. Current cannot flow from source to drain. Binary 0

Electric field creates conductive channel. Current flows freely. Binary 1

The Key Properties

- Voltage-controlled: A small voltage at the gate controls whether a much larger current can flow

- Amplification: The output can be stronger than the input, allowing signals to cascade

- Speed: Modern transistors switch in picoseconds (trillionths of a second)

- No mechanical parts: Nothing moves, meaning no wear and nearly infinite operations

Why Binary is Natural for Transistors

A transistor is either in saturation (fully ON, conducting maximum current) or in cutoff (fully OFF, conducting no current). These are its stable, low-power states. Operating in between wastes energy as heat and creates ambiguous signals. Binary computing exploits the transistor's natural behavior.

Moore's Law and Miniaturization

In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore observed that the number of transistors on integrated circuits was doubling approximately every two years. This observation, known as Moore's Law, has held remarkably true for over 50 years.

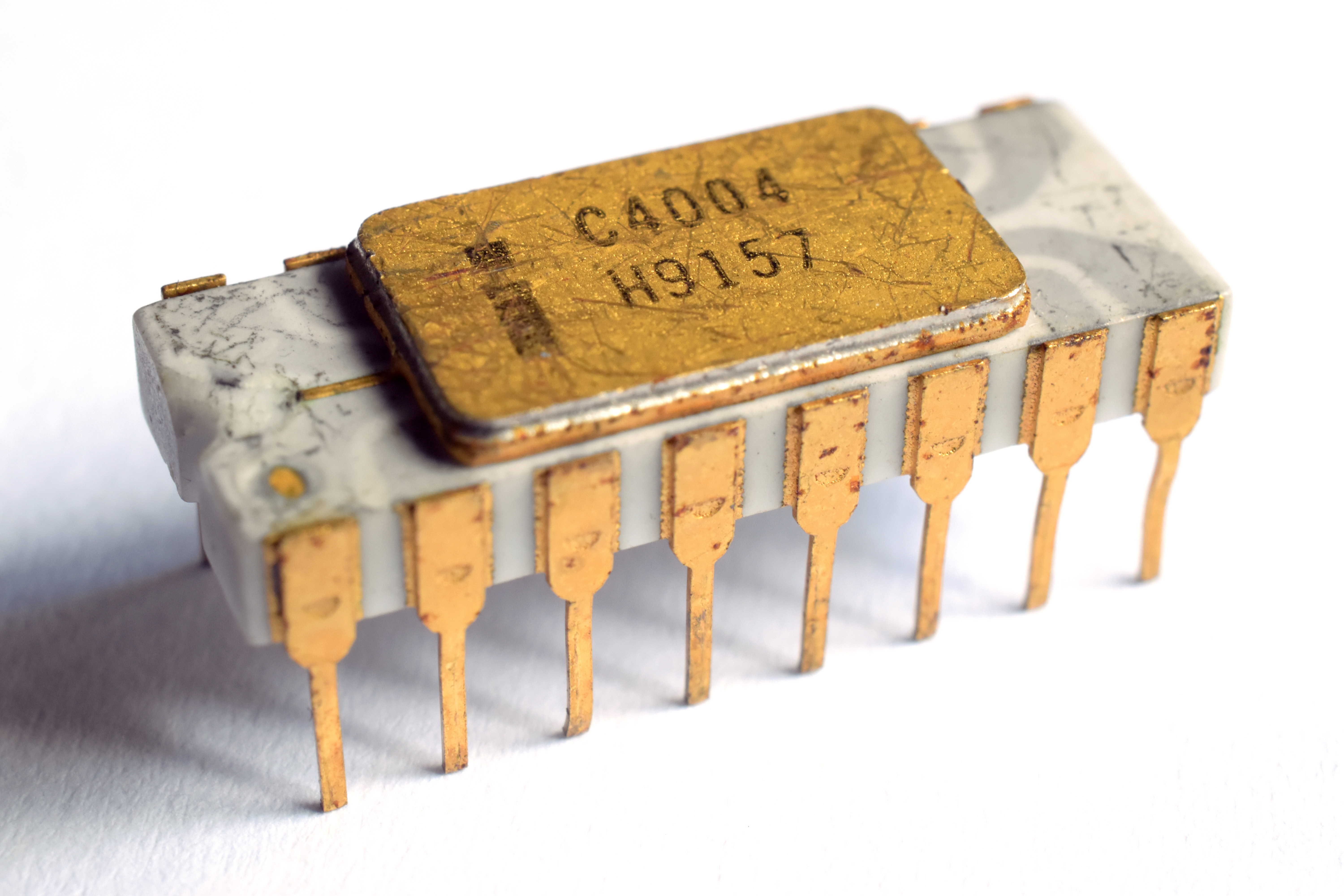

Intel 4004

2,300 transistors, 10 µm process

Intel 386

275,000 transistors, 1.5 µm process

Pentium 4

42 million transistors, 180 nm process

Intel Ivy Bridge

1.4 billion transistors, 22 nm process

Apple M2 Ultra

134 billion transistors, 5 nm process

To put this in perspective: the processor in your smartphone contains more transistors than there are stars in the Milky Way galaxy. Each of those transistors performs the same fundamental operation—switching between ON and OFF—billions of times per second.

Inside Modern Processors

A modern processor is a staggeringly complex orchestration of billions of binary switches. Let's examine what happens at the microscopic level:

Scale Comparison

Modern transistors are only about 25 silicon atoms wide. At this scale, we're approaching fundamental physical limits—quantum effects start to interfere with reliable operation.

FinFET: The Modern Transistor Architecture

Traditional planar transistors became unreliable below 22nm. Engineers developed 3D "fin" structures (FinFET) that wrap the gate around a raised channel, providing better control over electron flow. This innovation extended Moore's Law for another decade.

The Future: Beyond Silicon

As we approach atomic limits, researchers are exploring alternatives to conventional transistors:

Gate-All-Around (GAA) FETs

The next evolution beyond FinFET, where the gate completely surrounds the channel on all sides. Samsung and Intel are deploying these at 3nm nodes.

Carbon Nanotubes

Tubes of carbon atoms just 1nm in diameter could enable transistors far smaller than silicon allows. MIT demonstrated a working carbon nanotube processor in 2019.

Quantum Computing

Rather than binary bits, quantum computers use qubits that can exist in superposition of states. Not a replacement for classical computing, but a complement for specific problems.

Neuromorphic Chips

Processors designed to mimic the brain's neural structure, using analog signals and massive parallelism. Intel's Loihi chip demonstrates this approach.

Despite these innovations, binary logic will likely remain fundamental. Even quantum computers output classical binary results. The ON/OFF switch remains computing's essential abstraction.

Why Not Use More Than Two States?

If two states give us binary, why not use three states (ternary) or ten states (decimal)? It seems like more states would mean more information per component, requiring fewer components overall.

In theory, this is true. In practice, it fails for several reasons:

1. Noise Margins

With only two states, a signal can degrade significantly before being misread. With ten states, tiny variations cause errors. Binary is inherently noise-resistant.

2. Power Efficiency

Transistors in their fully ON or fully OFF states use minimal power. Intermediate states require constant current flow, generating heat and wasting energy.

3. Manufacturing Precision

Creating components with exactly two distinct states is far easier than creating components with many precise intermediate states.

4. Mathematical Elegance

Boolean algebra provides a complete, proven framework for logic operations. Multi-valued logic exists but is far more complex to implement.

The Bottom Line

Binary isn't a limitation—it's an optimization. By embracing the natural binary behavior of electronic components, engineers created the most reliable, efficient, and scalable computing systems possible.

Summary

From Claude Shannon's 1937 thesis to today's 5-nanometer processors, the story of electrical simplicity is one of embracing nature rather than fighting it. Electronic switches want to be either ON or OFF. By building computing systems that respect this fundamental property, humanity created machines of almost unimaginable capability.

The next time you use a smartphone, consider this: billions of tiny switches, each flipping between two states trillions of times per day, work in perfect coordination to create the digital experiences we take for granted. That's the power of electrical simplicity.